How Leadership Must Change in the Age of AI

How Leadership Must Change in the Age of AI

In the age of AI, the most important questions don’t produce answers—they produce coherence.

For much of modern business history, leadership was defined by cognitive advantage. Leaders were expected to know more, anticipate what was coming, make quick decisions, and resolve uncertainty through judgment. When intelligence was scarce, those who possessed it naturally rose to positions of authority.

That assumption no longer holds.

Artificial intelligence has made intelligence widely available and instantly accessible. Answers often appear before questions are fully formed. Analysis is generated at speed, sometimes without understanding. In this environment, standing out no longer requires depth—only fluency. As a result, the traditional model of leadership built on intellect alone is quietly eroding.

The challenge leaders face today is not simply adopting new technology. It is ensuring that the human side of work remains intact as everything accelerates.

By coherence, we mean people’s ability to remain grounded in their own judgment, connected to one another, and aligned on meaning as speed and complexity increase.

The Real Disruption Is Not AI, but Acceleration

AI does not disrupt organizations primarily by replacing jobs. Its more profound impact comes from acceleration. Decisions compress. Feedback loops shorten. Expectations rise. The pace of change often exceeds what people can emotionally and culturally integrate.

Leaders tend to notice this before it shows up in metrics. Meetings feel more efficient but less substantive. Decisions feel cleaner but less stable. Confidence rises even as trust quietly thins.

Good leadership today begins with recognizing that acceleration enters the human system before it appears on dashboards.

From Decision Authority to Interpretive Authority

In an AI-rich world, leaders are no longer the primary source of answers. Algorithms now outperform humans in areas that once required specialized expertise.

This may sound like a contradiction. Leaders were never meant to have all the answers—they were meant to ask the right questions. What has changed is not the value of inquiry, but the behavior of answers themselves. Answers now arrive instantly, confidently, and in abundance. Leadership no longer governs how answers are produced, but it remains responsible for how those answers are received, interpreted, and trusted.

When this interpretive role is absent, organizations drift. People defer to outputs they barely understand. They silence their instincts because the system sounds authoritative.

This dynamic is not abstract. In a widely cited medical case, an AI system and two physicians recommended discharging a patient who presented with chest pain. A nurse doubted the conclusion but deferred to the combined authority of the doctors and the machine. The patient died of a heart attack shortly after leaving the hospital. The failure was not technological. Human judgment was present—but overridden.

AI does not make us distrust technology. It makes us doubt ourselves.

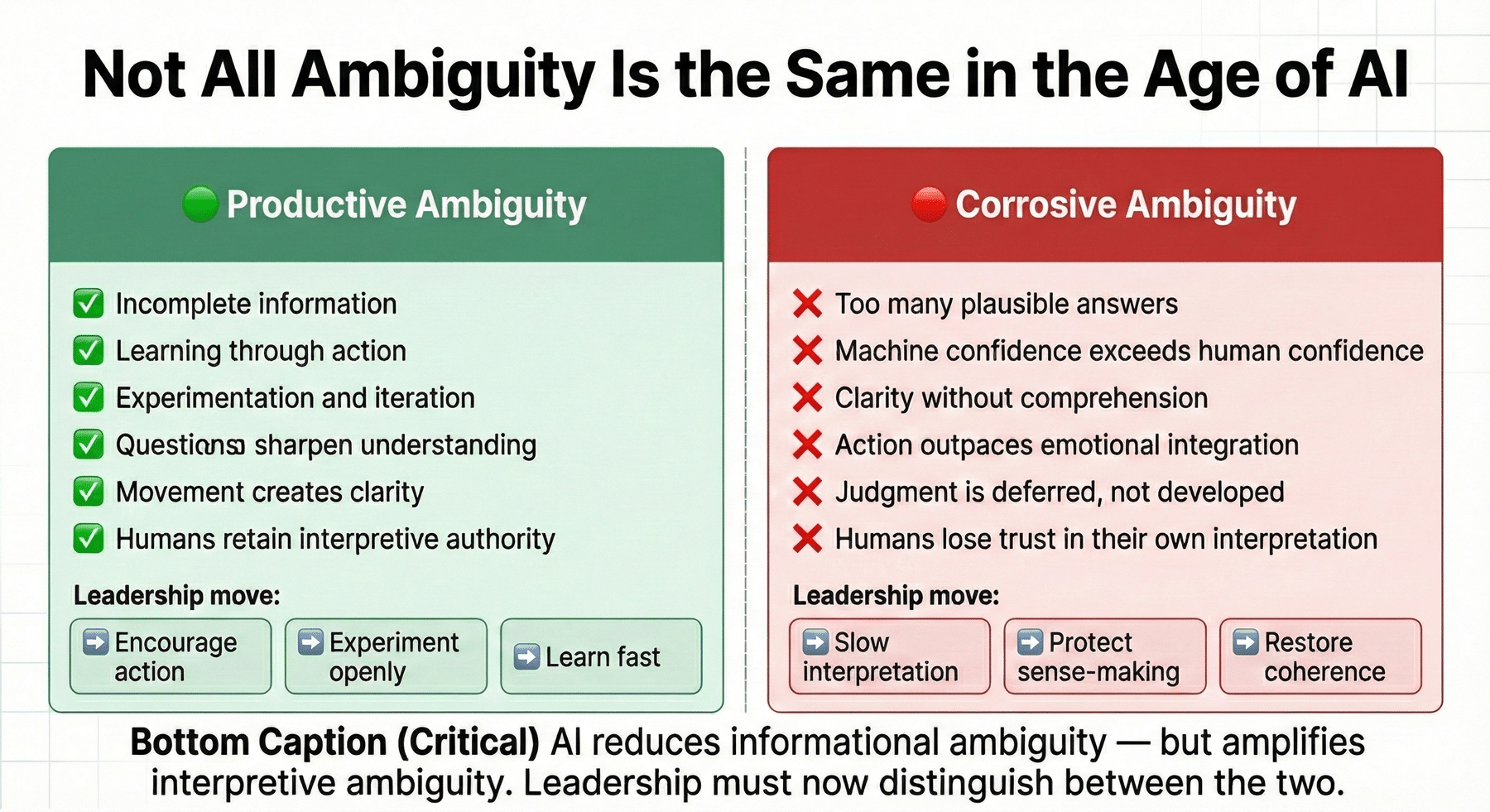

Why Leading Through Ambiguity Is No Longer Enough

For years, effective leadership was described as asking the right questions rather than having all the answers. This worked when intelligence was scarce, and inquiry slowed the system enough for people to integrate meaning.

AI changed those conditions.

Answers now surface independently of leadership, and at a pace no individual can regulate. Speed can increase confusion rather than resolve it. Information often moves faster than understanding.

This also changes the role of questions. In the past, a good question narrowed uncertainty and guided action. Today, questions often broaden the scope, revealing multiple interpretations and plausible paths forward. Leadership is no longer about asking questions that generate answers, but about asking questions that help people regain their bearings—questions that slow interpretation, surface meaning, and restore confidence in human judgment.

When answers are everywhere, leadership becomes the discipline of pacing: knowing which uncertainty to move through quickly and which must be held long enough for understanding to take root.

The Leader as Governor of Coherence

We see the same pattern repeatedly. Teams adopt AI tools, produce faster and better analyses, and still make poor decisions. The problem is not intelligence. It is confidence.

Recently, a management team completed a strategic review in record time because the AI-based assessment looked compelling. Three weeks later, they reconvened to redo the entire process after the situation quietly collapsed. The analysis wasn’t wrong. No one had stopped to ask whether they trusted it—or what it really meant.

This is the leadership shift underway.

A “governor of coherence” is not a new title. It is the leader who, when momentum builds because the answer looks clear, says, “Let’s slow this down.” Not because delay feels virtuous, but because premature certainty is expensive.

Under pressure, teams rarely fail for lack of information. They fail when communication stops. People defer. Judgment goes quiet. Trust erodes long before performance does.

Good leaders notice this early. They create real space—not symbolic space—for people to absorb what is happening and work through implications before moving on. They pay attention to the moment when speed makes people wonder whether they are still allowed to think for themselves.

This is not resistance to technology. That debate is already over. It is about whether people can use powerful tools without having their reasoning eclipsed.

Why Culture Matters More Than Capability Now

Most organizations still approach AI as a training problem: better tools, faster upskilling, new hiring profiles.

That framing misses the point.

When change moves faster than people can integrate it—not just learn it, but integrate it—culture determines whether teams hold together or fracture. We have watched groups of intelligent, capable individuals unravel because hesitation was labeled resistance and deliberation was dismissed as inefficiency. It does not take long for people to learn that conformity feels safer than judgment.

This is what we mean by emotional architecture. Not soft skills or sentiment, but the everyday infrastructure of how work actually happens. How pressure moves through the system. Whether disagreement is explored or smoothed over. Whether human judgment still carries weight when the system speaks confidently.

Short-term wins are possible without this. Metrics improve—output increases. But trust erodes beneath the surface, and eventually cohesion collapses.

Leaders who focus only on technical execution often notice too late. Those who pay attention to how decisions are made, how uncertainty is handled, and how meaning is constructed give their organizations a chance to move fast without breaking—that advantage compounds.

The Quiet Part of Leadership That Actually Matters

Much of what matters most in leadership today is invisible.

It is choosing presence over speed in a meeting and naming uncertainty instead of masking it with confidence. Saying to someone, “Trust your judgment here,” when the AI recommendation feels conclusive but incomplete.

None of this appears on dashboards. It does not scale neatly. Yet it shapes how people experience work when everything moves faster than they can keep up with.

As technology accelerates, the leadership qualities that matter most are not technical. They are human: steady, attentive, and patient in interpretation, even as speed begins to undermine judgment.

That is not softness. It is reliability.

What Really Counts Going Forward

In the coming years, leadership will be measured less by technological fluency and more by the ability to help people retain judgment, confidence, and agency as they work alongside increasingly capable systems.

AI will keep improving. That is a given.

The open question is whether organizations can remain coherent in the process.

Based on our observations, the central challenge is not technological. It is preserving the human conditions that enable people to think together under pressure—communication, trust, shared understanding, and the courage to speak up when something does not feel right.

That is what leadership means now.